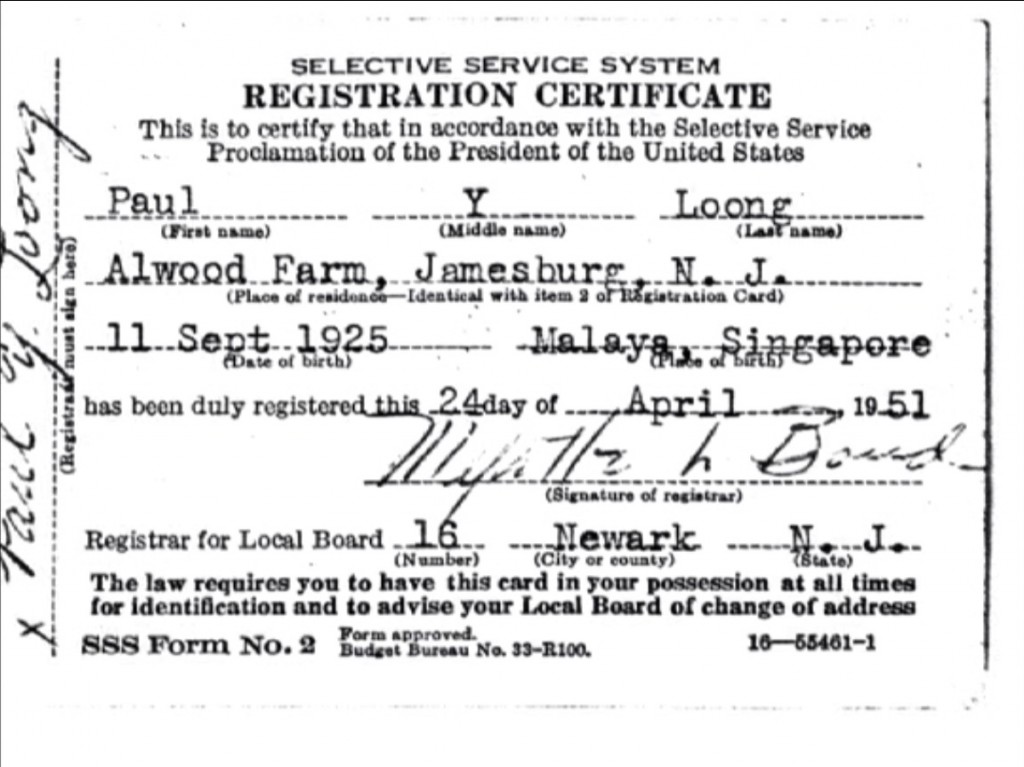

Since the Senate immigration bill was introduced this week, it’s a particularly relevant time to talk about how Dad actually got his citizenship. (This is kind of a long one.)

Previously, I covered his attempts to become a US citizen through service in the merchant marine and wartime US Army, both unsuccessful. In the first case, he was thwarted by the whim of an immigration bureaucrat; in the second, he failed because of 12 missing days.

Service Guarantees Citizenship? (Nope)

In HR 4233, later Public Law 86 [PDF], members of the Armed Forces serving after June 24, 1950 (the start of the Korean War), could become naturalized citizens — provided they served at least 90 days and were honorably discharged. No problem in either case for my dad.

However, the law also required people to have lived in the US for at least a full year prior to joining the military.

The relevant section of Public Law 83-86

According to the documentation, Dad had been in the US 12 days short of a year when he was drafted.

So instead of becoming a citizen upon discharge, he was nabbed by the INS for being an illegal alien.

Fortunately, he had money from his Army separation pay to post bond. So Dad went from the immigration office (at Columbus Circle) to the Bureau of Immigration of the National Catholic Welfare Conference (now part of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops), which had an office near the Seaman’s Institute, where he got the following advice:

Get down to Washington, DC and ask a member of Congress — in person — to sponsor a private bill for citizenship on his behalf. And do it as soon as possible.

He says that this is the best advice he ever got.

Help Me, Congress, You’re My Only Hope

Private bills are bills that affect specific people, not the entire public. They tend to deal with citizenship, tax relief, military awards, and veterans benefits, and aren’t as common as they used to be.

Like he says in the film, Dad took the train from New York Penn Station to Union Station in DC, and started knocking on doors of Congressmembers. He wasn’t wearing the double-breasted suit you see in some photos, or his military uniform — just simply dressed for the DC summer.

He was turned down at the first few offices he tried. Too busy, they said (he thinks he spoke to the actual Congressmen, not staffers.)

Congressman James C. Auchincloss. Public domain photo.

At the third or so office, that of James Auchincloss (R-New Jersey-3), he spoke to a woman at a desk, also simply dressed. Instead of a regular staffer, though, this was Lee Alexander Auchincloss — Mrs. Auchincloss. She said she’d ask her husband if he’d help. And he did.

(Sadly, Mrs. Auchincloss would die a few years later, in 1959. Mr. Auchincloss died in 1976, at the age of 91. I couldn’t find a photo of Mrs. Auchincloss, but here’s a small photo of the Congressman.)

If the Auchinclosses hadn’t agreed to help Dad, I’m fully convinced that he would have knocked on the doors of all 435 Representatives and 96 Senators (remember, Alaska and Hawaii weren’t yet states.) Which means he would have been visiting the offices of people like Representatives Sam Rayburn, Lloyd Bentsen, Gerald Ford, Tip O’Neil, and Senators Prescott Bush (father of George H. W.), Everett Dirksen, John F. Kennedy, Harry Flood Byrd, Hubert Humphrey, Strom Thurmond, Al Gore, Sr., and Lyndon Johnson.

HR 880 – Private Bill 147

Anyway, I won’t bore you with the full legislative history of the bill. Suffice it to say, the private bill was introduced as HR 6591 in the 83rd Congress. And it died. But because of Congressman Auchincloss’s intervention, the INS halted its deportation proceedings, and the bill was re-introduced in the 84th Congress as HR 880, and was approved July 7th, 1955:

HR 880: Approved July 7, 1955

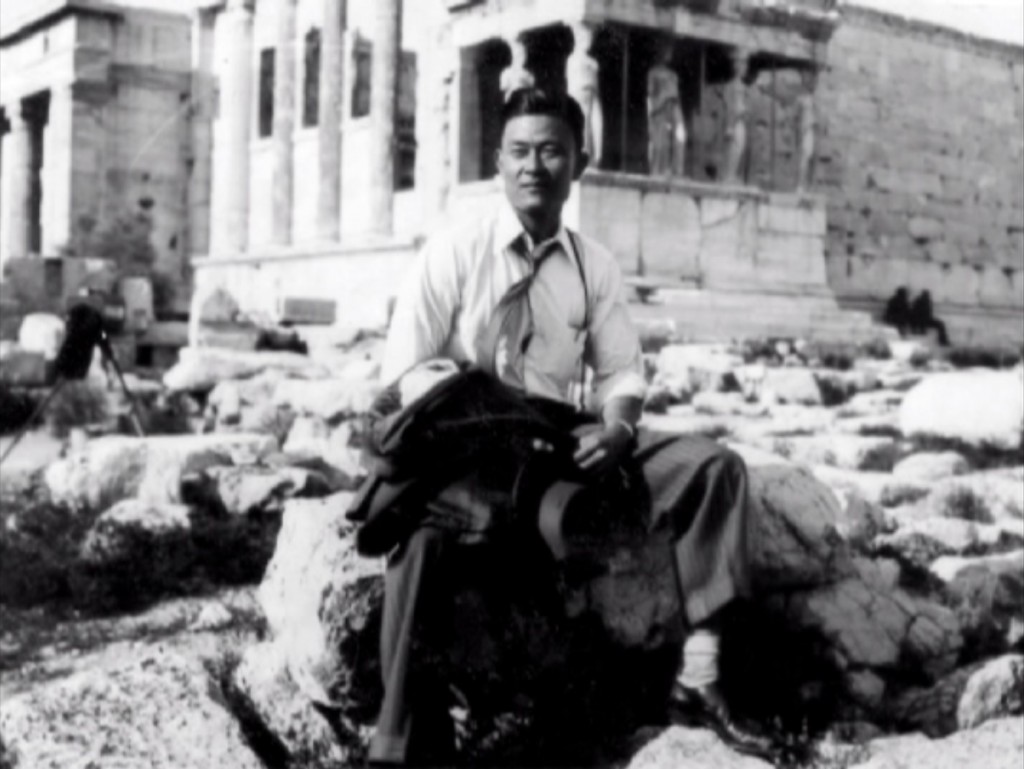

You know the rest of the story, or at least the result — Dad got naturalized and started the next chapters of his life.

Dad has copies of most of the relevant bills and correspondence. Plus, in 2012, I visited the National Archives, where with the help of a legislative librarian, I was able to find the files associated with the legislation, including the investigative reports, correspondence, letters of recommendation, and more.

Documents from the National Archives

So, that’s how it all went down.

The dates and the paper trail aren’t really important, just the compassion that one Congressman and his wife showed to a man who wasn’t even an a constituent, and was in fact, an illegal alien.

Next post: I’ll cherry-pick some tidbits from his life after getting citizenship, then wrap it all up on Sunday.

All photos in this post are screencaps from the film, Every Day Is a Holiday, and come from my father’s scrapbook. We’re working on digitizing and archiving all of them, including the captions he meticulously wrote in the margins.

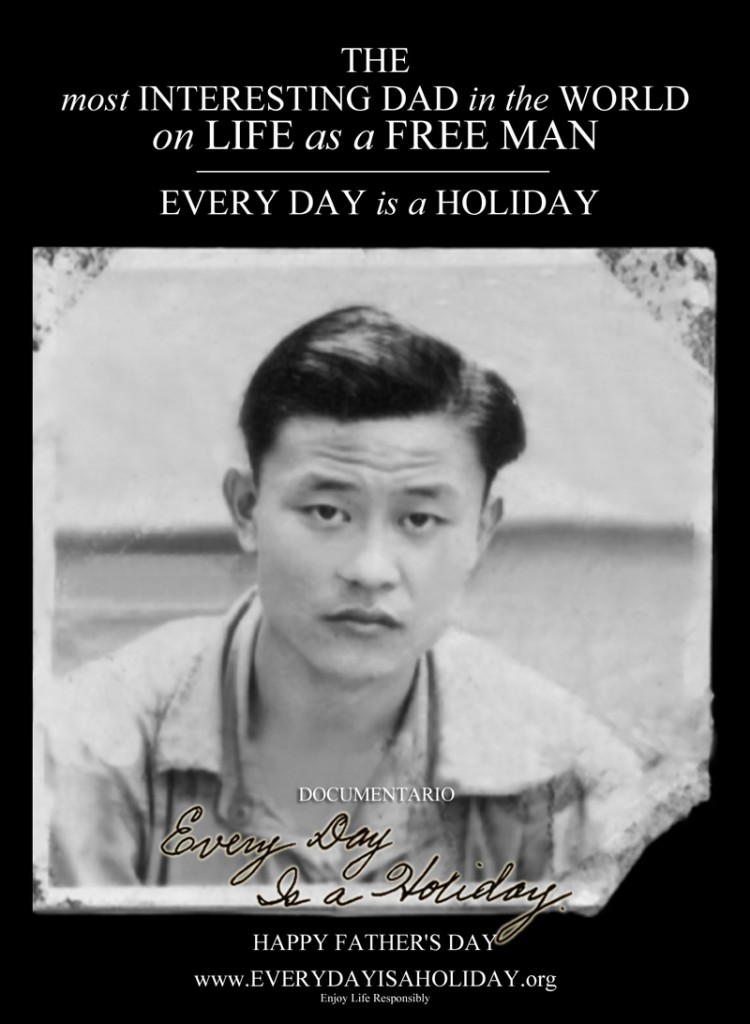

In the meantime, learn how to buy a copy of Every Day Is a Holiday on DVD, where you can also sign up to be notified when the film becomes available on premium streaming services and other events.